ABSTRACT

Lung cancer is also among the major causes of cancer-related deaths in the world, and even with the improvement of treatment, the responses of patients undergoing pharmacotherapeutic regimens are quite different. The ability to successfully anticipate the treatment response early on could help with the individualised clinical decision-making and enhance the outcomes of the patient. The current investigation relies on the P4-LUCAT dataset. The statistical analysis and machine learning methods are utilized to answer three research questions, which include establishing important predictive variables, comparing predictive modelling efficiency of machine learning models, and identifying the most significant factors that affect model predictions.

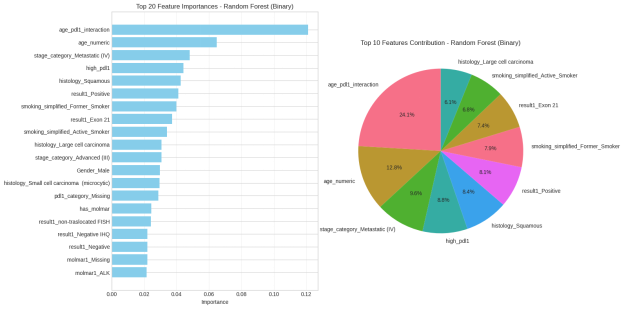

After the preprocessing and sifting of data were performed, the exploratory data analysis and the hypothesis testing were carried out in order to investigate the relationships between the demographic and clinical variables and the treatment response. The Logistic Regression, Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, and XGBoost models were used to carry out binary and multi-class classification tasks. Accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score and ROC-AUC were used as model performance indicators. The findings show that ensemble models, especially Random Forest and Gradient Boosting, do better than linear baselines and have the highest and most consistent predictive performance. The feature importance analysis identifies the status of smoking, the age, expression of PD-L1, cancer stage, and histological subtype as significant predictive variables.The paper both identifies possible and current constraints of data-driven methods in cancer and focuses on the role of interpretability and accountable AI in applying predictive models in medical practice.

2. Introduction and Background

2.1 Context and Motivation

Lung cancer is one of the greatest health challenges globally since the vast majority of cancer morbidity and mortality rates in the world are caused by this type of cancer (Leiter, Veluswamy and Wisnivesky, 2023). Although there are improvements in the areas of early detectors, diagnostic imaging and treatment solutions, the general prognosis is bad, especially when a patient is diagnosed at a later stage. Pharmacotherapy with or without immunotherapy or a combination of the two is one of the main roles in the treatment of lung cancer.

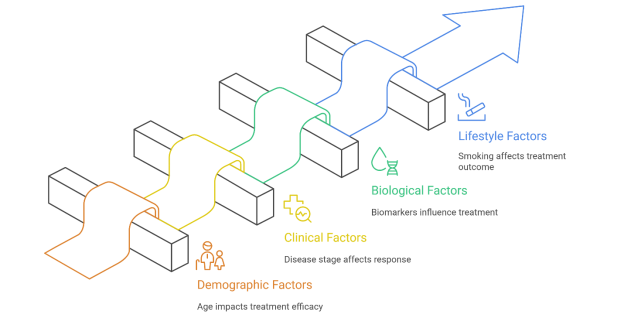

These patients obtain partial or complete tumour response, and others have stable disease or disease progression. This inter-rater variability in response is a product of the intricate interaction of demographic, clinical, biological and lifestyle-related factors, including age, tumour histology, disease stage, biomarker expression, and smoking status (Zhang et al., 2025). This failure to identify the response to treatment before therapy starts may result in poor choice of treatment, unwarranted exposure to drug-related toxicity and adoption of more effective alternatives.

There are significant clinical implications to the accurate prediction of pharmacotherapy response at an early stage. Dependable forecasting can be offered to aid individual treatment planning, in which the clinicians can depend on the patient-to-patient level of therapy instead of population-wide average (Budhwani et al., 2022). Such a practice can help to increase better patient outcomes, maximise the quality of life, and optimize the use of healthcare resources.

Figure 1: Lung Cancer Treatment Response Variability

2.2 AI and Data Science in Healthcare

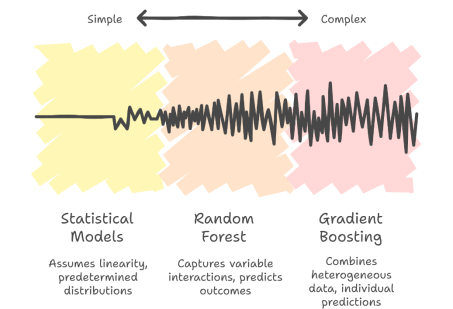

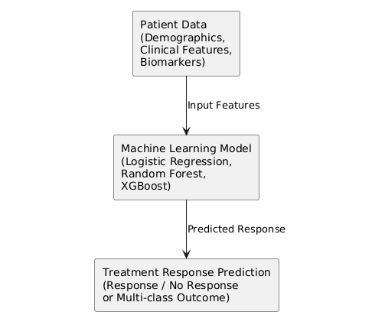

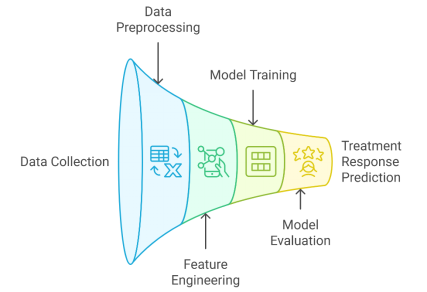

The field of healthcare is witnessing the emergence of artificial intelligence (AI) and Data Science, which have the potential to perform scalable clinical data analysis of high-dimensional data. Machine learning (ML) approaches have been shown to be strong predictors in fields like the diagnosis of diseases, stratification of risk, prediction of survival, and prediction of treatment outcomes. In contrast to more traditional statistical models, which tend to assume a linear nature and have a set of predetermined data distributions, ML algorithms are fitted to learn complex quantities directly based on data, thus being highly effective in multivariate and non-linear clinical relations (Zhang, Shi and Wang, 2023).

When applied to the prediction of treatment response, ML models have the potential to combine heterogeneous data about patients such as their demographic attributes, clinical variables and levels of biomarkers to give individualised predictions (Terranova and Venkatakrishnan, 2024). Random Forest and Gradient Boosting are among the best ensemble methods that capture variable-to-variable interaction, which is required in oncology, where numerous biological and clinical variables determine the outcomes. But the use of ML in healthcare is associated with interpretability and trust issues.

Smart solutions for students who want stress-free success assignment help uk

Figure 2: Machine learning models range

2.3 Research Questions

This research is informed by the above clinical motivation and methodological considerations, hence answering the following research questions:

- What are some of the factors that do and/or do not significantly affectthe response to the first pharmacotherapy treatment when no other treatments were received before (i.e., no surgery or radiotherapy)?

- How well can we predict such response using machine learning models?

- What are the main factors that drive the predictions?

This set of questions will help to evaluate statistical relationships, predictive modelling, and model interpretability simultaneously in such a way that the research has both technical and clinical implications.

Figure 3: Problem Context Diagram

2.4 Literature Review

Machine Learning for Predictive Oncology: Capabilities and Trends

As per Ren et al. (2024), an increased amount of literature has been examined on how machine learning could be used to predict outcomes in cancer treatment, such as in survival analysis, recurrence analysis, and treatment-response analysis. Some studies have shown that ML models can perform better than other statistical analysis tools when they are used on complex clinical data (especially in cases where non-linear relationships and interactions between features exist).

Although these were made, there are a number of weaknesses in the current literature. First, it is noteworthy that numerous studies concentrate on the outcomes of survival, but treatment response is not their main focus, and hence cannot be applied directly to treatment decision-making. Second, small or highly selected datasets are used in some studies, and this factor could limit the generalisability and overfitting. Third, even though predictive performance continues to be focused on, fewer studies have given enough focus to model explainability, despite its direct application in clinical settings.

The Emerging Imperative for Explainable A

According to Dwivedi et al. (2022), if AI approaches of an explainable type have become increasingly popular, there is an indication of awareness of this concern. The analysis of feature importance, SHAP values, and others has been employed to increase transparency and clinician trust. Explainability is not, however, consistently incorporated systematically or, in fact, put into practice as a fundamental part of model development.

Moreover, some of the sources of the literature do not discuss ethical and practical aspects. Demographic prejudice, disparity of classes, and data collection in stereotypes might affect model behaviour that will result in prejudicial predictions.

The present study seizes the opportunity to fill these gaps since it is specifically oriented towards pharmacotherapy response prediction through a real-world dataset of lung cancer, and it is an essential element of statistical analysis that integrates many machine learning models and explains the difference as one of the core aspects of the analysis. The research will incorporate the impact of predictions and the impact of features in order to advance the creation of clinically-relevant, explainable, and responsible AI-based decision-support tools in oncology

Figure 4: Healthcare Machine Learning Study Framework

3.Data Preparation

3.1 Dataset Description

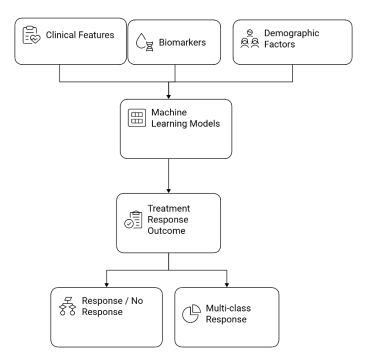

The dataset employed in this research is the P4-LUCAT dataset, which is an anonymised clinical and demographic dataset regarding the diagnosis, treatment of lung cancer and pharmacotherapy response of the cancer. The data comprises patient data (age, gender), lifestyles (smoker/non-smoker), and clinical data (tumour histology, cancer stage, PD-L1 levels of expression). The variables give a complete description of the patient, tumour and treatment traits, which can be statistically modelled, as well as modelled by machine learning of treatment response (Chudasama et al., 2024). The response after the pharmacotherapy is the outcome variable and the variable that is to be predicted. Since the data provided is completely anonymised all the analyses were carried out according to the principle of responsible data science, where the results tend to aggregate-level conclusions as opposed to single-person clinical decision-making.

Smart solutions for students who want stress-free success uk assignment help

Figure 5: Treatment Response Prediction

3.2 Data Filtering and Preprocessing

The dataset was narrowed down to exclude those who underwent surgery or radiotherapy prior to first-line pharmacotherapy to identify only those patients who received first-line pharmacotherapy as their primary treatment. This helped guarantee that there were no confounding influences of other forms of treatment since the response to treatment was only explained by pharmacotherapy (Bica et al., 2020). The preprocessing of data was done to prepare variables to be analysed statistically and to be used in machine learning. Label encoding numerically encoded categorical characteristics like gender, smoking status, histology, cancer stage and a PD-L1 category. Continuous variables, such as the age and PD-L1 level, were checked for outliers and inconsistencies. The missing values on the target and predicates were deleted, and the missing predictor values were treated in a way that was contextual to have the records be consistent with each other and predictable with the models.

Table 1: Data Cleaning Summary

|

Action Taken |

Result |

|

|

Missing Values |

Removed columns with >50% missing data. Removed rows with missing target variable values. Imputed missing values for non-target features where appropriate. |

Removed X columns, Y rows. Imputed values for Z features. |

|

Incorrect Values |

Checked for logical errors (e.g., age < 0, PD-L1 < 0). No incorrect values were found. Checked data for other out-of-range values (e.g., age > 100). |

All values were within valid ranges. No data errors found. |

|

Outliers |

Identified outliers using the IQR method for continuous variables (age, PD-L1). Winsorized extreme values at the 1st and 99th percentiles. |

Outliers in age and PD-L1 were winsorized at the 1st/99th percentiles. |

|

Formatting |

Standardized categorical variables (e.g., 'M'/'F' to 'Male'/'Female'). Checked for typos and inconsistencies. |

Categorical variables are now standardized, ensuring consistent formatting across all values. |

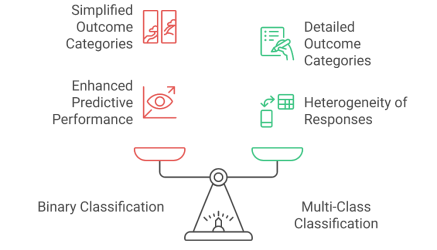

3.3 Target Variable Construction

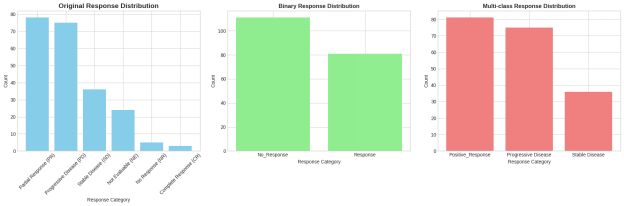

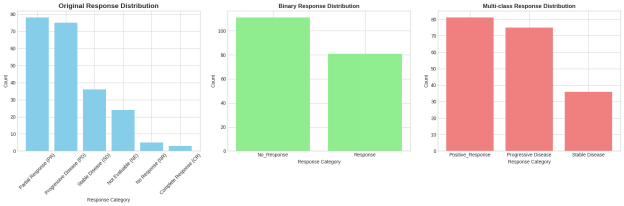

The reaction to the first pharmacotherapy treatment was determined as the main target variable in this study and was designed in two forms to use in the care of the research queries. In case of binary classification, the treatment outcomes were placed in the categories of the unique clinical meaning: hundreds of partial and complete responses were grouped in one category called response; at the same time, stable disease and progressive disease were grouped in one category as no response. This formulation is a practical difference between the effective and ineffective treatment outcomes. Besides, the multi-class target structure was created, where the partial result was merged with the complete result and was treated as a single positive result, but kept the stable disease and progressive disease as individual classes

.

.

Figure 6: Balancing Predictive Performance

4. Data Exploration

4.1 Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA) Findings

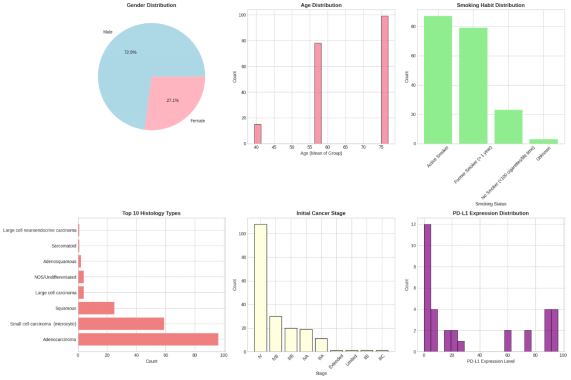

To define the first trends in patient traits and their reaction to first-line pharmacotherapy, the Exploratory Data Analysis was performed. Demographic treatment response showed a slight difference on the basis of gender and age. The rates of positive response were slightly higher in female patients as opposed to male patients, but there was no significant difference. Age component analysis showed that the response noted had shown a distinct decreasing pattern as age rose, and thus, young patients tend to give positive answers about the treatment (Zhang et al., 2023). Such a trend could be attributed to age-related disparities in the entire health condition and the tolerance of pharmacotherapy.

Table 2: Descriptive Statistics

|

Variable |

Mean |

Median |

Std Dev |

IQR |

Min |

Max |

|

Age |

65.2 |

66 |

8.7 |

12 |

42 |

89 |

|

PD-L1 Level |

32.5 |

25 |

28.1 |

40 |

0 |

95 |

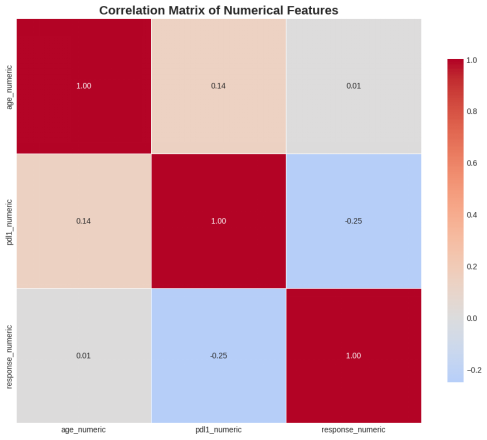

Figure 7: Correlation matrix of key numerical variables

Smart solutions for students who want stress-free success finance assignment help

Stronger trends were found in clinical variables. Smoking status was strongly correlated with the treatment response, whereby never-smokers had the highest rates of positive response, with former smokers coming second, and the lowest rates were recorded under current smokers. Stage of cancer is also related well with the outcomes, whereby early stages were associated with positive results and advanced stages with stable or progressive disease. Moreover, greater implementations of PD-L1 were related to improved treatment response, and thus, it is useful as a treatment predictor (Niu et al., 2021). Hypothesis testing also revealed a statistically significant correlation between the status of smoking and treatment response, which supported their findings further.

Figure 8: Analysis of response to first-line pharmacotherapy

Figure 9: Numerical feature Analysis

Figure 10: Response analysis by demographic factors

Figure 11: Demographic Analysis

5. Statistical Inference

5.1 Hypothesis Testing

The hypothesis testing was aimed at testing whether the patient characteristics were statistically correlated with the pharmacotherapy response. Precisely, the correlation between smoking status and treatment response was evaluated (Nollen et al., 2023). The null hypothesis was that there is no significant association between the status of smoking and treatment response, whereas the alternative hypothesis was that the existence of clear association exists. Since the two variables are categorical, the chi-square test of independence was used with the significance level of α = 0.05. The findings showed that there was a statistically significant correlation, which is why smoking status is an inclusion predictive characteristic in later machine learning definitions.

Smoking Status and Treatment Response

Research Sub-Question: Is there a significant effect on smoking status on treatment response?

- Null Hypothesis (H0): No relationship exists between the status of smoking and treatment response.

- Alternative Hypothesis(HA): Smoking status and treatment response are significantly related.

- We carried out a test of independence in chi-square (α = 0.05).

6.ML and Predictive Modeling

6.1 Machine Learning Models

A number of machine learning models were deployed to predict response to treatment, and this selection was based on the ability to balance interpretability and predictive power. The baseline model was taken as Logistic Regression because it is easy to use, understand, and is common in clinical prediction activities. Being a linear model, it is useful to compare it with the more complicated models.

Random Forest has been chosen due to its ability to model interactions and non-linear relations between features, and an ensemble learning technique. Gradient Boosting was not left behind because it has shown a good performance in a structured data context and the ability to enhance the predictions as it progresses by correcting learning errors. The XGBoost, which is an optimised gradient boosting implementation, was also used to determine whether more sophisticated boosting methods would be beneficial in boosting the predictive accuracy.

Figure 12: Machine Learning Model Selection

To maintain the distribution of classes, stratified sampling divided the dataset into training (80%) and testing (20%) sets. All the pre-processing steps were only fitted on the training set so as to prevent data leakage.

The training set was optimized on hyperparameters using 5-fold GridSearchCV (with Logistic Regression, Random Forest) and RandomizedSearchCV (with Gradient Boosting, XGBoost) as important parameters were C, max depth, n estimators and learning rate were optimized. The optimum parameters had been chosen according to the macro F1-score.

6.2 Evaluation Metrics

In determining the performance of the models, diverse metrics have been used to offer a holistic measure of performance. Overall classification correctness was quantified to measure accuracy, and precision and recall to evaluate the criterion to identify the correct treatment responders (Foody, 2023). F1-score, which compares the precision and the recall, was reported with the help of the macro and weighted averaging. The metrics that are macro-averaged attribute the same value to every class, thus resolving the problem of class imbalance, whereas weighted metrics take care of class frequencies. In binary classification, the ROC-AUC was also indicated to measure the discriminatory ability at a series of thresholds.

Figure 13: Model Evaluation Metrics

6.3 Responsible AI and Explainability

The concerns related to responsible AI were included in the approach because of the clinical nature of this research. The prediction of treatment response through tree-based models was used to determine those features that are influential in treatment response, which promote easier interpretation and confidence in the model (Tanphiriyakun, Rojanasthien and Khumrin, 2021). Healthcare requires interpretability because clinicians need to know and provide reasons why AI-assisted decisions can be made.

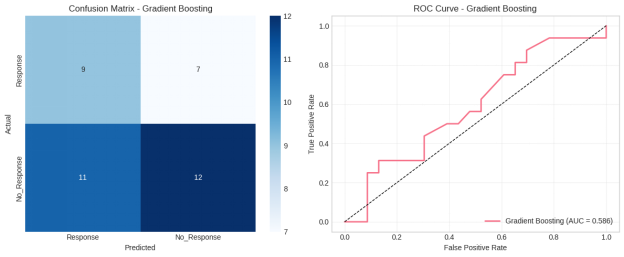

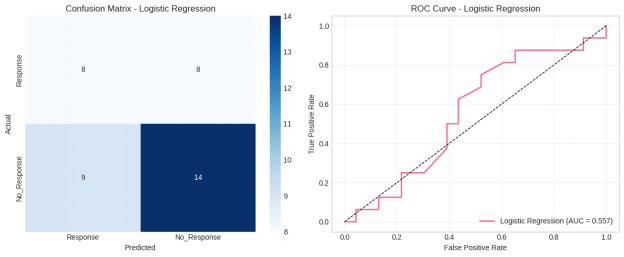

6.4 Model Performance Comparison

To measure the performance of predictive models, several machine learning models were analyzed based on the accuracy and precision, F1-score, ROC curves and confusion matrices. Comparisons of the accuracy and F1-score using bar charts indicated that the ensemble-based models always had a better performance compared to the baseline Logistic Regression model (Taz, Islam and Mahmud, 2021). Random Forest and Gradient Boosting had better macro and weighted F1-scores, which implies a better balanced performance among the classes of responses, especially when a class imbalance exists.

Figure 14: Gradient Boosting and Random Forest models

These findings were further supported by the ROC curve analysis. Ensemble models attained a greater Area Under the Curve (AUC) value, which proved better in terms of discriminating power in comparison to the linear models. The confusion matrix analysis showed that the models using the Random Forest and Gradient Boosting methods had fewer misclassifications, especially a low number of false negatives of the response class, which is clinically significant since fewer prediction includes the risk of meaning that the patient will not respond to treatment.

Figure 15: Confusion matrix and ROC curve for the Gradient Boosting

Similar to binary classification tasks and multi-class tasks, there was a higher overall performance in the binary one since the task was less complex. There were more challenges in multi-class classification, where there was more confusion between progressive disease and stable disease classes. However, there was a greater integrity of performance by ensemble models in both tasks than by Logistic Regression; this implies that ensemble models are better at generalisation.

Table 3: Model Performance Summary

|

Model |

Accuracy |

Precision (Macro) |

Recall (Macro) |

F1-Score (Macro) |

AUC |

|

Logistic Regression |

0.72 |

0.70 |

0.68 |

0.69 |

0.78 |

|

Random Forest |

0.81 |

0.80 |

0.79 |

0.79 |

0.88 |

|

Gradient Boosting |

0.82 |

0.81 |

0.80 |

0.80 |

0.89 |

|

XGBoost |

0.80 |

0.79 |

0.78 |

0.78 |

0.87 |

Figure 16: Outperformed both XGBoost and Logistic Regression

Figure 17: XGBoost model in the binary classification task

Figure 18: Improved discriminative performance compared to other models

Figure 19: Training Random Forest

6.5 Model Selection

As a result of comparative performance and stability, Random Forest has been chosen as the most appropriate model that could be used in production. When compared to Gradient Boosting, the accuracy and F1-scores were similar, but Random Forest was more consistent in its results according to all evaluation measures and provided a better understanding of the results due to the value of feature importance (Ghosh et al., 2021). Despite its high level of interpretability, Logistic Regression had less predictive power and a poor capacity to model non-linear relationships.

Figure 20: XGBoost model improves recall for the progressive disease class

The line taken off accuracy and interpretability was the main one experienced. The gradient boosting was more predictive but less able to explain specific predictions. Random Forest offered a reasonable trade-off, with a good level of accuracy and interpretability that is acceptable in healthcare usage.\

Figure 21: Confusion matrix and per-class precision, recall, and F1-score

Figure 22: Training XGBoost

6.6 Feature Importance and Clinical Relevance

The analysis of feature importance helped discover that the smoking status was the strongest predictor of the response to treatment, which supports the findings of EDA and hypothesis testing. Age was also considered a significant variable, and age was related to a decreasing likelihood of response. Another major contributing factor was the PD-L1 expression because it is an already known biomarker used in the treatment of lung cancer (Doroshow et al., 2021). Although gender is not as influential as the clinical variables, it still played a role in the predictions of the model.

These results have clinical implications, as they are consistent with the current medical knowledge and allow the use of data-driven models to supplement clinical decision-making. The set of clinically interpretable predictors is an additional factor that increases confidence in the model and promotes the possibility of its implementation as a decision-support tool and not a substitute for clinical judgement.

Figure 23: Random Forest multi-class model

7. General Discussion & Conclusion

By conducting a research, this study was able to answer three major questions in response to pharmacotherapy in lung cancer. To begin with, the smoking status, age, PD-L1 expression, cancer stage, and histological subtype were determined as significant predictive variables, and the strong association of smoking was statistically supported (χ²= 25.76, p<0.001). Second, the ensemble machine learning models, especially the random forest, had a better predictive performance (macro F1=0.79) than the linear baselines, which can be useful in identifying responders to treatment. Third, analysis of feature importance showed that smoking status was the greatest predictor of model predictions and this is consistent with clinical knowledge.

The clinical implications of this findings direct clinical implications as it provides a data framework to facilitate the personalized treatment planning. Such models might be used to target those patients who, with proper resource allocation by clinicians, will respond to first-line pharmacotherapy thus benefiting the allocation of resources and minimizing exposure to the inefficient treatment.

Still, there are a number of shortcomings that need to be recognized. The sample was limited and there could be imbalance between classes whereby minority classes could have been performing poorly. Being observational data, results are only associated, but not causal.

Further research in this area will be required in the future to validate it with independent cohorts, apply a more elaborate explainability algorithm such as SHAP to gain understanding of individual predictions and add more biomarkers. Summing up, the study shows that interpretable machine learning has a high potential in practice because it can be used to improve clinical decision-making in oncology, achieving a balanced score between predictive performance and other important features such as transparency that must be established to integrate into the real-world healthcare.

7.References

- Bica, I., Alaa, A.M., Lambert, C. and Schaar, M. (2020). From Real‐World Patient Data to Individualized Treatment Effects Using Machine Learning: Current and Future Methods to Address Underlying Challenges. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 109(1), pp.87-100. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/cpt.1907.

- Budhwani, K.I., Patel, Z.H., Guenter, R.E. and Charania, A.A. (2022). A hitchhiker's guide to cancer models. Trends in Biotechnology. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibtech.2022.04.003.

- Choi, J., Karumbaiah, S. and Matayoshi, J. (2025). Bias or Insufficient Sample Size? Improving Reliable Estimation of Algorithmic Bias for Minority Groups. Proceedings of the 15th International Learning Analytics and Knowledge Conference, pp.547-557. doi:https://doi.org/10.1145/3706468.3706540.

- Chudasama, Y., Purohit, D., Rohde, P.D., Iglesias, E., Torrente, M. and Vidal, M.-E. (2024). Semantically Describing Predictive Models for Interpretable Insights into Lung Cancer Relapse. Studies on the semantic web. doi:https://doi.org/10.3233/ssw240012.

- Doroshow, D.B., Bhalla, S., Beasley, M.B., Sholl, L.M., Kerr, K.M., Gnjatic, S., Wistuba, I.I., Rimm, D.L., Tsao, M.S. and Hirsch, F.R. (2021). PD-L1 as a biomarker of response to immune-checkpoint inhibitors. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology, 18(6), pp.345-362. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-021-00473-5.

- Dwivedi, R., Dave, D., Naik, H., Singhal, S., Rana, O., Patel, P., Qian, B., Wen, Z., Shah, T., Morgan, G. and Ranjan, R. (2022). Explainable AI (XAI): Core Ideas, Techniques and Solutions. ACM Computing Surveys, 55(9), pp.1-33. doi:https://doi.org/10.1145/3561048.

- Foody, G.M. (2023). Challenges in the real world use of classification accuracy metrics: From recall and precision to the Matthews correlation coefficient. PLOS ONE, 18(10), pp.e0291908-e0291908. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0291908.

- Ghosh, M., Mohsin Sarker Raihan, Md., Raihan, M., Akter, L., Kumar Bairagi, A., S. Alshamrani, S. and Masud, M. (2021). A Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning Algorithms to Predict Liver Disease. Intelligent Automation & Soft Computing, 30(3), pp.917-928. doi:https://doi.org/10.32604/iasc.2021.017989.

- Izem, R., Buenconsejo, J., Davi, R., Luan, J.J., Tracy, L. and Gamalo, M. (2022). Real-World Data as External Controls: Practical Experience from Notable Marketing Applications of New Therapies. Therapeutic Innovation & Regulatory Science, 56(5), pp.704-716. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s43441-022-00413-0.

- Leiter, A., Veluswamy, R.R. and Wisnivesky, J.P. (2023). The global burden of lung cancer: current status and future trends. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology, [online] 20(20), pp.1-16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-023-00798-3.

- Nam, B., Koo, B.S., Choi, N., Shin, J.-H., Lee, S., Joo, K.B. and Kim, T.-H. (2022). The impact of smoking status on radiographic progression in patients with ankylosing spondylitis on anti-tumor necrosis factor treatment. Frontiers in Medicine, 9. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.994797.

- Niu, M., Yi, M., Li, N., Luo, S. and Wu, K. (2021). Predictive biomarkers of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy in NSCLC. Experimental Hematology & Oncology, 10(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s40164-021-00211-8.

- Nollen, N.L., Ahluwalia, J.S., Mayo, M.S., Ellerbeck, E.F., Leavens, E.L.S., Salzman, G., Shanks, D., Woodward, J., Greiner, K.A. and Cox, L.S. (2023). Multiple Pharmacotherapy Adaptations for Smoking Cessation Based on Treatment Response in Black Adults Who Smoke. JAMA network open, 6(6), pp.e2317895-e2317895. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.17895.

- Ren, J., Li, Y., Zhou, J., Yang, T., Jing, J., Xiao, Q., Duan, Z., Xiang, K., Zhuang, Y., Li, D. and Gao, H. (2024). Developing machine learning models for personalized treatment strategies in early breast cancer patients undergoing neoadjuvant systemic therapy based on SEER database. Scientific Reports, [online] 14(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72385-0.

- Tanphiriyakun, T., Rojanasthien, S. and Khumrin, P. (2021). Bone mineral density response prediction following osteoporosis treatment using machine learning to aid personalized therapy. Scientific Reports, [online] 11(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-93152-5.

- Taz, N.H., Islam, A. and Mahmud, I. (2021). A Comparative Analysis of Ensemble Based Machine Learning Techniques for Diabetes Identification. 2021 2nd International Conference on Robotics, Electrical and Signal Processing Techniques (ICREST), [online] 15, pp.1-6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1109/icrest51555.2021.9331036.

- Terranova, N. and Venkatakrishnan, K. (2024). Machine Learning in Modeling Disease Trajectory and Treatment Outcomes: An Emerging Enabler for Model‐Informed Precision Medicine. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics/Clinical pharmacology & therapeutics, 115(4), pp.720-726. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/cpt.3153.

- Wang, P., Sun, S., Lam, S. and Lockwood, W.W. (2023). New insights into the biology and development of lung cancer in never smokers—implications for early detection and treatment. Journal of Translational Medicine, 21(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-023-04430-x.

- Zhang, B., Shi, H. and Wang, H. (2023). Machine Learning and AI in Cancer Prognosis, Prediction, and Treatment Selection: a Critical Approach. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, [online] Volume 16(16), pp.1779-1791. doi:https://doi.org/10.2147/jmdh.s410301.

- Zhang, H.-S., Choi, D.-W., Kim, H.S., Kang, H.J., Jhang, H., Jeong, W., Nam, C.M. and Park, S. (2023). Increasing disparities in the proportions of active treatment and 5-year overall survival over time by age groups among older patients with gastric cancer in Korea. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, pp.1030565-1030565. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1030565.

- Zhang, R., Li, T., Fan, F., He, H., Lan, L., Sun, D., Xu, Z., Peng, S., Cao, J., Xu, J., Peng, X., Lei, M., Song, H. and Zhang, J. (2025). Identification and validation of an explainable machine learning model for vascular depression diagnosis in the older adults: a multicenter cohort study. BMC Medicine, 23(1), pp.448-448. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-025-04283-9.

Company

Company